| |

|

Build is Tony Fadell story on how develop careers, lives and products that matter.

Takeaway Points

Build Yourself

The best way to find a job you’ll love and a career that will eventually make you successful is to follow what you’re naturally interested in, then take risks when choosing where to work. Follow your curiosity rather than a business school playbook about how to make money. Assume that for much of your twenties your choices will not work out and the companies you join or start will likely fail. Early adulthood is about watching your dreams go up in flames and learning as much as you can from the ashes. Do, fail, learn. The rest will follow.

A company that’s likely to make a substantial change in the status quo has the following characteristics:

- It’s creating a product or service that’s wholly new or combines existing technology in a novel way that the competition can’t make or even understand.

- This product solves a problem — a real pain point — that a lot of customers experience daily. There should be an existing large market.

- The novel technology can deliver on the company vision — not just within the product but also the infrastructure, platforms, and systems that support it.

- Leadership is not dogmatic about what the solution looks like and is willing to adapt to their customers’ needs.

- It’s thinking about a problem or a customer need in a way you’ve never heard before, but which makes perfect sense once you hear it.

If you’re not solving a real problem, you can’t start a revolution. A glaring example is Google Glass or Magic Leap — all the money and PR in the world can’t change the fact that augmented reality (AR) glasses are a technology in search of a problem to solve.

The key is persistence and being helpful. Not just asking for something, but offering something. You always have something to offer if you’re curious and engaged. You can always trade and barter good ideas; you can always be kind and find a way to help.

A good mentor won’t hand you the answers, but they will try to help you see your problem from a new perspective. They’ll loan you some of their hard-fought advice so you can discover your own solution.

Don’t (Only) Look Down

The CEO and executive team are mostly staring way out on the horizon — 50 percent of their time is spent planning for a fuzzy, distant future months or years away, 25 percent is focused on upcoming milestones in the next month or two, and the last 25 percent is spent putting out fires happening right now at their feet. They also look at all the parallel lines to make sure everyone is keeping up and going in the same direction.

Managers usually keep their eyes focused 2–6 weeks out. Those projects are pretty fleshed out and detailed, though they still have some fuzzy bits around the edges. Managers’ heads should be on a swivel — they often look down, sometimes look further out, and spend a fair amount of time looking side to side, checking in on other teams, making sure everything’s coming together for the next milestone.

Junior individual contributors spend 80 percent of their time looking straight down—maybe a week or two out—to see the fine points of their day-to-day work. In the early stages of your career, that’s the way it should be. You should be focused on getting your specific piece of each project done, done well, and out the door. Your executive team and managers are supposed to be looking out for roadblocks. They’re supposed to warn you so you can adjust course, or at least grab a helmet. But sometimes they don’t. So 20 percent of the time, individual contributors need to look up (look beyond the next deadline or project and forward to all the milestones coming up in the next few months. Then look all the way down to your ultimate goal: the mission. Ideally it should be the reason you joined the project in the first place. As your project progresses, be sure the mission still makes sense to you and that the path to reach it seems achievable.). And they need to look around (get out of your comfort zone and away from the immediate team you’re on. Talk to the other functions in your company to understand their perspectives, needs, and concerns. This internal networking is always useful and it can give you an early warning if your project is not headed in the right direction.). The sooner they start, the faster and higher they’ll advance in their career.

Build Your Career

If you’re thinking of becoming a manager, there are six things you should know:

- You do not have to be a manager to be successful. Many people assume that the only path to more money and stature is managing a team. However, there are alternatives that will enable you to get a similar paycheck, have similar amounts of influence, and possibly be happier overall. Of course if you want to be a manager because you think you’ll love it, then absolutely pursue it. But even then, remember that you don’t have to be a manager forever. I’ve seen plenty of people go back to being individual contributors, then turn around and be managers again in their next job.

- Remember that once you become a manager, you’ll stop doing the thing that made you successful in the first place. You’ll no longer be doing the things you do really well—instead you’ll be digging into how others do them, helping them improve. Your job will now be communication, communication, communication, recruiting, hiring and firing, setting budgets, reviews, one-on-one meetings (1:1s), meetings with your team and other teams and leadership, representing your team in those meetings, setting goals and keeping people on track, conflict resolution, helping to find creative solutions to intractable problems, blocking and tackling political BS, mentoring your team, and asking “how can I help you?” all the time.

- Becoming a manager is a discipline. Management is a learned skill, not a talent. You’re not born with it. You’ll need to learn a whole slew of new communication skills and educate yourself with websites, podcasts, books, classes, or help from mentors and other experienced managers.

- Being exacting and expecting great work is not micromanagement. Your job is to make sure the team produces high-quality work. It only turns into micromanagement when you dictate the step-by-step process by which they create that work rather than focusing on the output.

- Honesty is more important than style. Everyone has a style—loud, quiet, emotional, analytical, excited, reserved. You can be successful with any style as long as you never shy away from respectfully telling the team the uncomfortable, hard truth that needs to be said.

- Don’t worry that your team will outshine you. In fact, it’s your goal. You should always be training someone on your team to do your job. The better they are, the easier it is for you to move up and even start managing managers.

A lot of engineers only trust other engineers. Just like finance people only trust finance people. People like people who think like them.

One of the hardest parts of management is letting go. Not doing the work yourself. You have to trust your team—give them breathing room to be creative and opportunities to shine. But you can’t overdo it—you can’t create so much space that you lose track of what’s going on or are surprised by what the product becomes. Even if your hands aren’t on the product, they should still be on the wheel. Examining the product in great detail and caring deeply about the quality of what your team is producing is not micromanagement.

Data vs Opinion

Most people don’t even want to acknowledge that there are opinion-driven decisions or that they have to make them. Because if you follow your gut and your gut is wrong, then there’s nowhere else to cast blame. But if all you did was follow the data and you still failed, then clearly something else was wrong. Someone else screwed up. This is often a tactic of people who are trying to cover their asses. It’s not my fault! I just went where the data sent me! The data doesn’t lie!

Here are a few reasons why a leader may sit on your idea and then call in the consultants:

- Delay. They may be waiting for something—a promotion or a bonus—and don’t want to take a risk until they get it.

- Fear for their job. They may be convinced that the consequence of failure is that they’ll lose this project or their position or—if the failure is spectacular enough—their job.

- They don’t have the time or don’t want to bother. They don’t believe it’s worth the effort to dig in and really understand the decision, choose from the array of options before them, and take a risk. They just want someone else to do it and make them look smart.

- They know what they want but don’t want to hurt anyone’s feelings. They want to be seen as “nice” so they’ll just keep testing the water, asking for more data again and again until you’re worn out and exasperated.

So what do you do when you’re stuck with a manager who’s hell-bent on driving off a cliff, ideally while throwing all their money out the window at some consultants Storytelling is how you get people to take a leap of faith to do something new. It’s what all our big choices ultimately come down to—believing a story we tell ourselves or that someone else tells us. Creating a believable narrative that everyone can latch on to is critical to moving forward and making hard choices. It’s all that marketing comes down to. It’s the heart of sales. And right now you’re selling—your vision, your gut, your opinion.

Assholes

Throughout your career, you’ll encounter some real assholes. These are (mostly) men and (sometimes) women who come in different flavors of selfish or deceitful or cruel, but have one unifying characteristic: you cannot trust them. They can and will screw you and your team over, either to get something for themselves or just to push you down and make themselves look like the hero.

Here are the different assholes you might have to deal with:

- Political assholes: The people who master the art of corporate politics, but then do nothing but take credit for everyone else’s work. These assholes are typically incredibly risk averse—they’re focused exclusively on surviving and pushing others down so they can reach the top. They don’t make anything themselves — are absent for the real work and tough decisions — but they’ll happily leap in to cry “I told you so” when anybody else’s project has a hiccup, then try to swoop in to “fix” it. They often won’t speak up in large meetings because they never want to be seen by their bosses as being wrong. Instead they’ll work in the background to undermine you and everyone else who isn’t on their “team.” These assholes usually build a coalition of budding assholes around them — copycats who see it as their path to success. And there’s always one person who they hate and plot against and have to push out of the way somehow.

- Controlling assholes: Micromanagers who systematically strangle the creativity and joy out of their team. These assholes can never be reasoned with. They resent any good idea that didn’t come from them and are extremely threatened by anyone on their team who is more talented than they are. They never give people credit for their work, never praise it, and often steal it. These are the assholes who dominate big meetings — who won’t let you get a word in edgewise, and who get defensive and angry if anyone critiques their ideas or suggests alternatives. These assholes are sometimes really good at what they do — they hone their skills to a fine point, then use it to cut down everyone around them. The only thing you can do when dealing with controlling assholes is: : Kill ’em with kindness. Ignore them. Try to get around them. Quit.

- Asshole assholes: They suck at work and everything else. These are the mean, jealous, insecure jerks who you’d avoid at a party, but who inevitably sit immediately next to you at the office. They cannot deliver, are deeply unproductive, so they do everything possible to deflect attention away from themselves. They will lie, craft gossip, and manipulate others to get people off their scent. The only good thing about these assholes is that they’re generally out the door pretty quickly—they can only deflect for so long before people start noticing that they bring zero value. And nobody likes working with them. These types of assholes can be divided into 2 main categories depending on how they tend to respond once confronted: Aggressive, or Passive-Aggressive.

- Mission-driven “assholes”: The people who are crazy passionate — and a little crazy. They speak most frankly, trampling the politics of the modern office, and steamroll right over the delicate social order of “how things are done around here.” Much like true assholes, they are neither easygoing nor easy to work with. Unlike true assholes, they care. They give a damn. They listen. They work incredibly hard and push their team to be better—often against their will. They are unrelenting when they know they’re right, but are open to changing their minds and will praise other people’s efforts if they’re genuinely great. A good way to know if you’re working with a mission-driven “asshole” is to listen to the mythos around them — there are always a few choice stories floating around about some crazy thing they’ve done, and the people who’ve worked with them closely are always telling everyone that they’re not that bad, really. Most tellingly, the team ultimately trusts them, respects what they do, and looks back at the experience of working with them fondly, because they pushed the team to do the best work of their lives.

Quitting

Here’s how you know when its time to quit:

- You’re no longer passionate about the mission.

- You’ve tried everything. You’re still passionate about the mission but the company is letting you down.

And I want to make it very clear: hating your job is never worth the money.

Build Your Business

Every product should have a story, a narrative that explains why it needs to exist and how it will solve your customer’s problems. A good product story has three elements:

- It appeals to people’s rational and emotional sides.

- It takes complicated concepts and makes them simple.

- It reminds people of the problem that’s being solved — it focuses on the “why.”

The virus of doubt is a way to get into people’s heads, remind them about a daily frustration, get them annoyed about it all over again. If you can infect them with the virus of doubt — “Maybe my experience isn’t as good as I thought, maybe it could be better” — then you prime them for your solution. You get them angry about how it works now so they can get excited about a new way of doing things.

Another approach to remember is that analogies can give customers superpowers. A great analogy allows a customer to instantly grasp a difficult feature and then describe that feature to others. That’s why “1,000 songs in your pocket” was so powerful. Everyone had CDs and tapes in bulky players that only let you listen to 10–15 songs, one album at a time. So “1,000 songs in your pocket” was an incredible contrast—it let people visualize this intangible thing—all the music they loved all together in one place, easy to find, easy to hold—and gave them a way to tell their friends and family why this new iPod thing was so cool.

Evolution Versus Disruption Versus Execution

- Evolution: A small, incremental step to make something better.

- Disruption: A fork on the evolutionary tree — something fundamentally new that changes the status quo, usually by taking a novel or revolutionary approach to an old problem.

- Execution: Actually doing what you’ve promised to do and doing it well. Your version one (V1) product should be disruptive, not evolutionary. Even if you do execute your idea well, it may not be enough. If you’re revolutionizing a major, dug-in industry, you may also need to disrupt marketing or channel or manufacturing or logistics or the business model or something else that never occurred to you.

If your company is disruptive, you have to be prepared for strong reactions and stronger emotions. Some people will absolutely love what you’ve made. Some people will violently, relentlessly hate it. That’s the danger with disruption. It is not welcome by everyone. Disruption makes enemies.

Disruptions are an extremely delicate balancing act. When they fall apart it’s usually for one of three reasons:

- You focus on making one amazing thing but forget that it has to be part of a single, fluid experience. So you ignore the million little details that aren’t as exciting to build—especially for V1—and end up with a neat little demo that doesn’t actually fit into anyone’s life.

- Conversely, you start with a disruptive vision but set it aside because the technology is too difficult or too costly or doesn’t work well enough. So you execute beautifully on everything else but the one thing that would have differentiated your product withers away.

- Or you change too many things too fast and regular people can’t recognize or understand what you’ve made.

Three Generations

Keep in mind there are three stages of profitability:

- Not remotely profitable: With the first version of a product you’re still testing out the market, testing out the product, trying to find your customers. Many products and companies die at this stage before they ever make a dime.

- Making unit economics or gross margins: Hopefully with V2 you can make a gross profit with each product sold or each customer who subscribes to your service. Keep in mind that fantastic unit economics are not enough to make a profitable company. You’ll still be spending a ton of money just running your business and acquiring customers through sales and marketing.

- Making business economics or net margins: With V3 you have the potential to make net profits with each subscription or product sold. That means that what you take in in sales revenue outstrips your business costs, so your company as a whole makes money.

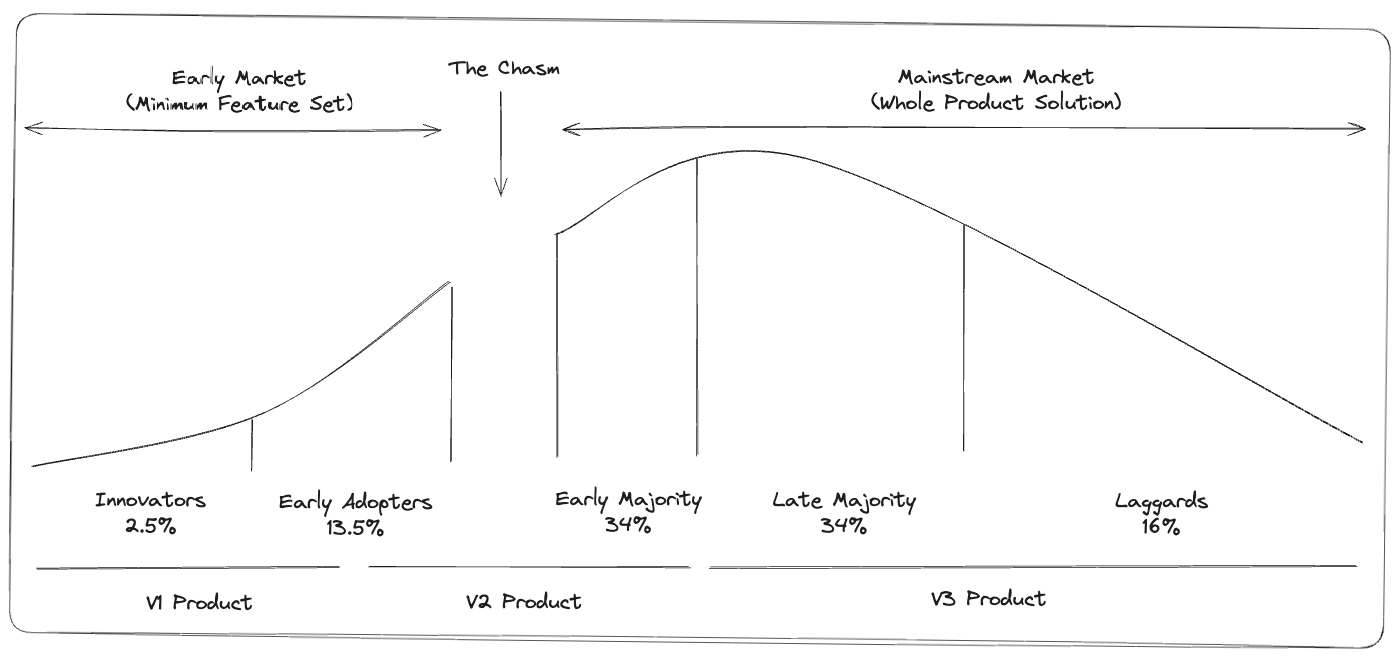

Crossing the Chasm introduced the world to the famous Customer Adoption Curve chart below. The idea behind it is pretty simple: a small percentage of customers will jump to buy a new product early regardless of how well it works—they just want the latest doohickey. However, most will wait until it’s been around for a while and all the kinks have been worked out.

Figure 1: Crossing the Chasm

| V1 | V2 | V3 |

|---|---|---|

| Who is it for? | ||

| Innovators and early adopters | Early Majority | Late majority and laggards |

| Product | ||

| You are essentially shipping your prototype | You are fixing the stuff you screwed up with V1 | You are refining an already great product |

| Outsourcing vs Building in house | ||

| Figuring things out and outsourcing | Start bringing more things in house | Lock internal expertise and selectively outsource smaller projects |

| Product | ||

| Product market fit | Profitable product | Profitable Business |

How to Spot a Great Idea

There are three elements to every great idea:

- It solves for “why.” Long before you figure out what a product will do, you need to understand why people will want it. The “why” drives the “what.”

- It solves a problem that a lot of people have in their daily lives.

- It follows you around. Even after you research and learn about it and try it out and realize how hard it’ll be to get it right, you can’t stop thinking about it.

The best ideas are painkillers, not vitamins. Vitamin pills are good for you, but they’re not essential. You can skip your morning vitamin for a day, a month, a lifetime and never notice the difference. But you’ll notice real quick if you forget a painkiller.

Do I have what it takes to create a successful startup? Should I launch my project within a big company instead? The answer is that you’ll never know until you take the leap and try. But here’s how to get as ready as you’ll ever be:

- Work at a startup.

- Work at a big company.

- Get a mentor to help you navigate it all.

- Find a co-founder to balance you out and share the load.

- Convince people to join you. Your founding team should be anchored by seed crystals—great people who bring in more great people.

Every time you raise capital, you should think of it as a marriage: a long-term commitment between two individuals based on trust, mutual respect, and shared goals.

Be CEO

There are generally three kinds of CEOs:

- Babysitter CEOs are stewards of the company and are focused on keeping it safe and predictable. They generally oversee the growth of existing products that they inherited and don’t take risks that might scare executives or shareholders. This invariably leads to the stagnation and deterioration of companies. Most public company CEOs are babysitters.

- Parent CEOs push the company to grow and evolve. They take big risks for larger rewards. Innovative founders — like Elon Musk and Jeff Bezos — are always parent CEOs. But it’s also possible to be a parent CEO even if you didn’t start the business yourself—like Jamie Dimon at JPMorgan Chase or Satya Nadella at Microsoft.

- Incompetent CEOs are usually either simply inexperienced or founders who are ill-suited to lead a company after it reaches a certain size. They are not up to the task of being either a babysitter or a parent, so the company suffers.

You don’t have to be an expert in everything. You just have to care about it. No matter your leadership style, no matter what kind of person you are — if you want to be a great leader, you have to follow that one cardinal rule. The other commonalities of successful leaders are just as straightforward:

- They hold people (and themselves) accountable and drive for results.

- They’re hands-on, but to a point.

- They know when to back off and delegate.

- They can keep an eye on the long-term vision while still being eyeball-deep in details.

- They’re constantly learning, always interested in new opportunities, new technologies, new trends, new people. And they do it because they’re engaged and curious, not because those things may end up making them money.

- If they screw up, they admit to it and own their mistakes.

- They’re not afraid to make hard decisions, even when they know people will be upset and angry.

- They (mostly) know themselves.

- They have a clear view of both their strengths and challenges.

- They can tell the difference between an opinion- and data-driven decision and act accordingly.

- They realize that nothing should be theirs, even if the genesis was with them. It all has to be the team’s. The company’s. They know their job is to jubilantly celebrate everyone else’s successes, to make sure they get credit for them, and hold little for themselves.

- They listen. To their team, to their customers, to their board, to their mentors. They pay attention to the opinions and thoughts of the people around them and adjust their views when they get new information from sources they trust.

Boards

Bad boards come in all shapes and sizes and screw up in a million different ways. But they generally fall into three categories:

- Indifferent boards occur when a majority of the board members are checked out. Sometimes an investor sits on a bunch of different boards and has a “you win some, you lose some” mentality — and has already put your company in the loss column. Sometimes board members are motivated for the wrong reasons — they want their payout and don’t really care about the company or its mission. Sometimes they see obvious issues with the CEO but just don’t want to do the work to remove them. Because it is work — paperwork and emotional fallout, then the search to replace the CEO, the interviews, the headaches, the internal transitions, the press, the cultural crises. They say, “It’s not really that bad, is it?” and everyone suffers with the status quo because nobody feels like stepping up to fix it.

- Dictatorial boards are the opposite — too invested, too controlling. They hold the reins so tightly that the CEO doesn’t have the freedom to lead independently. Many times the board includes a previous founder (or two or three) who still wants control. So the CEO ends up behaving more like a COO — taking orders, fulfilling requests, keeping the trains running but not having much say in where they go.

- Inexperienced boards are made up of people who don’t know the business, don’t know what a good board or CEO looks like, and are incapable of asking the CEO hard questions, never mind removing them. These boards are often too scared to act decisively. The investors worry that if they challenge the CEO, they won’t get to invest in the next funding round or they’ll get a reputation for firing founders and new startups won’t want to work with them. Typically companies with inexperienced boards are always running out of money. They never meet their quarterly goals and always blame “market problems” rather than the CEO or themselves. They don’t know how to bring in new talent and new expertise and just smile and nod their way to collapse.

So when you’re choosing your board members, here’s what types of people you should be considering:

- Seed crystals: Just as you need seed crystals to grow your team, you want someone on the board who knows everyone, has done it before, and can suggest other amazing people to add to the board or to your company. A seed crystal points out what your board is missing and tells you who to call, or just calls them for you.

- A chairperson: This isn’t a must, but it can be helpful. A chairperson sets the agenda, leads the meetings, herds the cats. Sometimes the CEO is the chairperson, sometimes another board member is, sometimes there’s no formal chairperson at all. A chairperson is the CEO’s closest relationship on the board, a mentor and a partner. They help the CEO through issues they have with other board members, or they step in when the business gets hairy and the team gets scared. They’ll attend employee meetings and give them the board’s perspective on how the company is doing—they’ll say, “The CEO’s not going anywhere, she’s doing a great job.” Or “The board’s not worried about the recent sales, and you shouldn’t be, either. We can’t wait to invest again.” Or sometimes, “Yes this person has left, but the company will be okay. Here’s the plan that the board supports.”

- The right investors: When you’re picking investors, you’re also picking one or two of them to be board members. So you don’t want investors who think only in numbers and dollar signs and don’t understand the slog and grind of creation. Find investors who are experienced in the work you do and empathetic to how difficult it is to get right. Find human beings who you’d love to have dinner with. If you have an interesting enough company, you can talk to your investors in advance and select the person the firm will put on your board. Sometimes CEOs don’t take the top-dollar investment deal, to ensure that they get a better board member.

- Operators: These are people who have been in your position before and know the roller coaster of company building. When the investor board members start hammering you for not hitting your numbers, the operator board members can step in and explain the realities of the situation. They can talk about how nothing ever goes according to plan. Then they can help you forge a new plan with new techniques and new tools.

- Expertise: Sometimes you’ll need someone who deeply understands something very specific—patents, B2B sales, aluminum manufacturing, whatever — but they’re too experienced or too entrenched in their current project to take a job at your company. So the only way to get them is through a spot on your board.

Benefits vs Perks

Keep in mind there’s a difference between benefits and perks:

- Benefit: Things like a 401(k), health insurance, dental insurance, employee savings plans, maternity and paternity leave—the things that really matter and can make a substantive impact on your employees’ lives.

- Perk: An occasional pleasant surprise that feels special, novel, and exciting. Free clothes, free food, parties, gifts. Perks can be completely free or subsidized by the company.

If you want to give employees a perk, keep in mind two things:

- When people pay for something, they value it.

- If something is free, it is literally worthless. So if employees get a perk all the time, then it should be subsidized, not free. If something happens only rarely, it’s special. If it happens all the time, the specialness evaporates. So if a perk is only received occasionally, it can be free. But you should make it very clear that this is not going to be a regular occurrence and change up the perk so it’s always a surprise.

Quotes

Steve Jobs once said of management consulting, “You do get a broad cut at companies but it’s very thin. It’s like a picture of a banana: you might get a very accurate picture but it’s only two dimensions, and without the experience of actually doing it you never get three dimensional. So you might have a lot of pictures on your walls, you can show it off to your friends—I’ve worked in bananas, I’ve worked in peaches, I’ve worked in grapes—but you never really taste it.”

“The only failure in your twenties is inaction. The rest is trial and error.” — ANONYMOUS

“Great companies are bought, not sold.” - Bill Campbell

“I can’t make you the smartest or the brightest, but it’s doable to be the most knowledgeable. It’s possible to gather more information than somebody else.”

Book Authors: Tony Fadell

Contacts

If you want to keep updated with my latest articles and projects follow me on Medium and subscribe to my mailing list. These are some of my contacts details: