Contents

- LLMs Pitfalls

- Introduction

- Fine-tuning

- Decoding Strategy

- Efficient LLM Deployment

- Guardrails

- LLM Serving Metrics

- Advanced RAG

- Conclusion

AI Generated (Image by Author).

LLMs Pitfalls

An introduction to some of the key components surrounding LLMs to produce production-grade applications

Introduction

Since the rise of ChatGPT, Large Language Models (LLMs) have become more and more popular also for non-technical people. Although LLMs on their own cannot provide yet a full product ready to be served to a vast audience. As part of this article, we will cover some of the key elements that are used to make LLMs production-ready.

Fine-tuning

Datasets

Models like LLAMA are able to predict next tokens in a sequence although this doesn’t necessarily make them suited for tasks such as question answering. Therefore in order to optimize these models different types of datasets can be used:

Raw completion: if the goal is predicting the next token we provide some input text and let the model progressively predict the upcoming steps.

Fill in the middle objective: in this case we have some starting and ending text and the model is learning to fill the gap. This approach is quite popular to create code completion models like Codex.

Instruction datasets: the goal here is to teach the model how to answer questions. We have questions (instructions) as input and answers as output.

Preference datasets: typically used with Reinforcement Learning for ranking the different possible answers to a question. In this case, there can be multiple plausible answers to a question and the objective is to find the best outcome.

Classification datasets: By adding a final classification head and finetuning the LLM with a classification dataset we can finally make the model behave as a classifier.

Techniques

There are two main approaches to fine-tuning LLMs: Supervised Fine-Tuning and Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback.

Supervised Fine-Tuning: the LLM is trained on a set of input-output pairs and the weights iteratively adjusted to minimize the difference between the predicted and actual output. Small high-quality sets of input-output pairs can result in great model improvements compared to less curated bigger sets. The 3 most common options to perform supervised fine-tuning are: full fine-tuning, LoRA, and Quantized LoRA.

Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback: the LLM learns by interacting with the environment and getting feedback. The objective is to maximize the overall reward, which in this case is provided by human evaluators reviewing the predictions.

If designed correctly, Reinforcement Learning from Human Feedback can usually yield better results than Supervised Fine-Tuning although it can be difficult to get the setup correctly (e.g. reward system) and ensure the human feedback is always consistent. Therefore, a lot of research focus is currently on developing preference learning mechanisms on Supervised Fine-Tuned models.

Decoding Strategy

LLMs Decoding Strategy is one of the most overlooked key parameters used to decide the text to generate. There are 4 key types of Decoding Strategies in use:

Greedy Search: the most likely token is always picked as the selected next token. This approach maximize therefore short term reward over long term results, making it difficult to find a global maximum. With Greedy search in fact, we don’t care about computing different possible sequences of words and pick the best one but just recursively pick the most likely word at each step. On the other hand, this makes this approach really computationally efficient and fast.

Top-k sampling: improving on Greedy Search, we can take advantage of the probability distribution created by the LLM when predicting a next token selecting the K top likely tokens and sampling one from them as our choice. Taking this approach we can then be able to make our output sequence less predictable. Another possible way to increase randomness is by varying the Temperature parameter (altering therefore probabilities).

Nucleus sampling: another way to take advantage of probabilities is instead by sorting tokens by their likelihood and keep the first N tokens that add up to a chosen probability value (e.g. keep top tokens which probability adds up to 90%). The output can then be selected by random sampling from this list. Because probabilities are used to determine the length of the list, taking this approach can lead to greater variation in the output.

Beam Search: in this case, we create N beams of most likely tokens. The length of each sequence can then be determined by a maximum length or end of a sentence token. The beam with the highest score is then selected as the sequence of choice.

Efficient LLM Deployment

Two of the key LLM bottlenecks are their memory/computational requirements and low paralleziability (e.g. autoregressive output generation).

A common approach to solve the first issue is to use quantization (lowering the precision of LLMs parameters to for example 8 or 4 bit). There are 2 key approaches to perform quantization: Post Training Quantization (PTQ) and Quantization Aware Training (QAT). With PTQ, we take the weights of a pre-trained model and just lower their precision. In QAT instead, we perform the quantization process directly during the training/fine-tuning time. This is of course more expensive to do but also usually yields better accuracy results. Further information about quantization techniques can be found in this article. In addition to quantization, also LLM pruning (structured/unstructured) or distillation can be applied.

To improve low paralleziability issues instead we can mainly focus on performing architectural improvements to our LLMs. Some common approaches include: Multi-Query Attention, Grouped Query Attention, Rotary Embeddings, etc… Finally, LLM latency can generally be reduced by increasing sparsity (e.g. Mixture of Experts, Structured Pruning), fusing adjacent operators and caching (e.g. saving attention layers intermediate keys/values).

Guardrails

As LLMs are trained on a lot of data publicly available on the internet, they can potentially also be used to perform malicious tasks such as helping commit different forms of crimes. In addition to this, LLMs are also specifically trained to support users (even if they might not have the right answer) and might therefore hallucinate. To avoid these sorts of issues, managed LLM providers have been implementing different forms of guardrails to steer the LLM in the right direction.

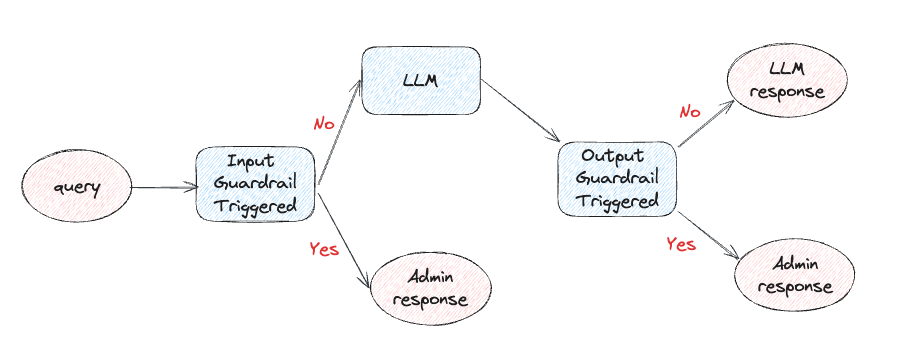

Guardrails can be applied either in the input (report malicious content before it is actually shown to the LLM) or output (check the LLM response before showing it to the user). It is important to notice that every time we add any sort of guardrail we are introducing latency and increasing the overall cost of answering a query (Figure 1).

Figure 1: LLM Guardrails Workflow (Image by Author).

Some examples where input guardrails can be applied are: identify off-topic questions and redirect the user to ask only appropriate questions, preventing jailbreaking attempts overriding the prompt, avoiding injection of malicious code (e.g. a user asking an LLM to validate/execute some malicious code).

One way to reduce latency when working with input guardrails is then to trigger asynchronously the guardrail check and LLM call and return the guardrail check if triggered instead of the LLM output.

Finally, some examples of output guardrails include:

Preventing hallucination by providing the LLM with some additional context about the query or with past examples of hallucinated responses to not repeat.

Check if the output syntax is consistent (e.g. provided code is able to execute, JSON/CSV output is well structured, etc.)

Introducing output specifications to agree with specific company branding and policies (of the company providing the LLM-powered services).

LLM Serving Metrics

Once deployed an LLM it is then important to not just track the performance of the model itself in giving good answers but also other side metrics that might impact the overall user experience (e.g. inference speed). Some examples of common metrics to keep in mind (especially for real-time systems) include:

Time to first token: time the user has to wait to see the first token appearing. It is important to notice that increasing the throughput of the system we can be able to handle more requests at the same time but as a side effect, we also tend to increase the time to first token.

Time per output token: once the first token appears, we can then measure the time taken to generate a token for each of the users using the system.

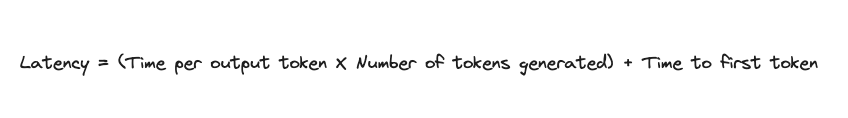

Latency: measures the total time to get a full response. This can be calculated by multiplying the time per output token by the number of tokens generated and adding the result to the time to first token (Figure 2).

Figure 2: LLM Latency Formula (Image by Author).

Advanced RAG

Retrieval-augmented Generation (RAG) has risen to be one of the key approaches in order to develop Generative AI use cases in a business context. RAG can in fact be much more computationally/cost effective in the short term than fine-tuning an LLM on a business-specific topic and can also greatly help to reduce the likelihood of hallucinations.

To make the best use out of RAG, it is then vital to structure an infrastructure able to reliably provide the best possible context to support an LLM input.

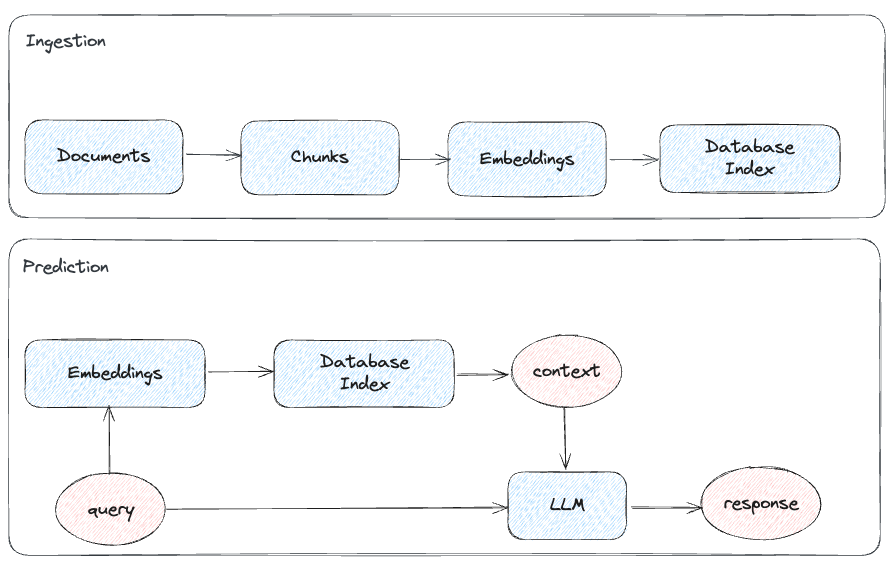

The most basic approach for RAG involves in taking your company proprietary data, dividing it into different chunks, creating an embedding representation for each of them, and indexing the result in a database/vector store. When a new query arrives, we can then look at our database for relevant content and pass it to the LLM alongside the original user query (Figure 3). As part of the process, the context to feed the LLM can optionally be re-ranked in order to meet some explicit business rules/preferences.

Figure 3: Basic RAG Workflow (Image by Author).

From the above diagram we can then infer there are 3 main variables we can tweak to improve the performance of our system: query (make the input easier to understand for an LLM), context (provide relevant and well-structured context) and LLM response (make sure the response is adequately supported by the context and relevant with respect to the original query).

Input queries can be improved for example by: decomposing the original query into multiple sub-queries to solve sequentially or converting the original query to a more general version and use the output as context to answer the original query.

Some approaches to improve RAG context instead include:

Sentence-window retrieval: we don’t provide the LLM with just the retrieved chunk from the search but also pass some sentences before and after the chunk to provide more context. This is better than using longer and overlapping chunks from the start since with smaller chunks we can be more sure to find the most relevant chunk during the retrieval process.

Auto-merging retrieval: a hierarchy of parent-child chunks is defined and if a good number of retrieved child chunks are linked to the same parent then the parent is used as the context of the LLM instead of the children.

Additionally, also other parts of the pipeline can be optimized by for example: testing different chunk sizes, trying different types of embeddings to use to process the chunks, or searching indexing mechanisms (e.g. brute-force flat index, FAISS, ANNOY, HNSW, ElasticSearch, Pinecone, etc.). In particular, if working with big databases of documents it can also be quite useful to have multiple hierarchical indexes instead of a single index to speed up the search process for the context to pass to the LLM. For example, in the first index, we could store the summary of each document (or hypothetical questions someone could ask about that document) and in the second index, the different chunks composing the document in question and retrieve from there only the relevant chunk. Finally, it is important to remember that keyword-based search (e.g. TF-IDF) is always an option and that it can also be used in a hybrid format to enhance Generative AI based semantic search.

Once our system is live, we can then be able to use user feedback to improve the retrieval process by training an embedding adaptor (a small ANN that can be inserted in the bigger pre-trained model).

Conclusion

As part of this article, we introduced just some of the caveats to consider when working with LLMs, although as the field keeps evolving there is always more that can be done (e.g. Model Merging, Mixture of Experts, State Space Models like Jamba, Agents, Hardware Optimization, etc.). If you have any other caveat you would like to see added, feel free to leave a comment below!

Contacts

If you want to keep updated with my latest articles and projects follow me on Medium and subscribe to my mailing list. These are some of my contacts details: